“The Weight of the Dead” by Brian Hodge is a dystopian science fiction novelette taking place years after all electronics have been fried by the sun. Two siblings live in an enclave with their father, who’s about to be punished for a crime, sparking fierce but secret rebellion by the daughter.

As was their custom, as the law said, as it came down yesterday in judgment, they strapped her father to the corpse at midday, when the sun was at its highest overhead.

Melody had spent the night wondering, well, what if it was cloudy. Hoping for this like she’d never hoped for anything. Maybe it would make a difference if nobody could see the sun. The law seemed firm about where it had to be. If they didn’t know, maybe they’d have to wait, if only another day. But when it came to a death sentence, one more day was everything.

By the time she’d awakened this morning, she was ready to admit that it wouldn’t have made any difference. No sun, just clouds—this was something a kid would pin her hopes on, and Melody was no kid. She was fourteen, almost, and maybe she’d never been one to begin with. She held Jeremy’s little hand snug as they watched the straps come out, feeling him grind the bones in her fingers together, and thought maybe there were no such things as kids at all in this world.

Kids were just something that used to live in the World Ago, before the Day the Sun Roared.

“In life, each of us must make room on our back for our brother, for our sister,” Bloomfield was saying. He was a big, stooped man with a big head. He postured like he was reading from a bulky book he held in front of him, but he never seemed to actually look at it. “Carrying one another toward each and every tomorrow is the only way we’ll continue to survive. It’s the only way we ever have.”

Here in the center of the village, gathered around the Thieves Pole, they had her father kneel, leaning forward onto his knuckles. Melody supposed it went easier this way, but then, how would she know? This had never happened as far back as she could remember. Only about once every ten years, her grandmother had told her. That was about how long it took for somebody to forget. Forget the lesson that the entire village was obliged to turn out and watch. Forget what the punishment was like, really like, in the end. Somebody was bound to forget, eventually.

But why why why did it have to be her father?

“As in life, then, so in death,” Bloomfield said.

Her father didn’t look up at her, at Jeremy, just knelt on the ground staring at the browning October grass, his hair hanging down in front of his forehead. Three hundred pairs of eyes all around him, gazing in pity and horror and hatred, depending on how they’d felt about the dead man.

Probably not a lot of hate, come to think of it.

She wanted him to look at her, and she didn’t. What if he saw that she wasn’t crying and thought she no longer loved him? She’d cried over her dog—she couldn’t cry for him? Could be she was still too shocked to cry. She’d never believed it would actually come to this.

While her father posed like a tilted table, they draped Tom Harkin’s body over his back, the dead man’s sightless eyes staring at the back of her father’s head, the near-naked corpse’s belly to his spine. The straps they used were designed to not be cut—not easily, anyway—made of rough rawhide that surrounded a core of chains. They looped the first strap over the both of them like a belt that wrapped around and around and around, then padlocked it to itself. There were more straps that crisscrossed at the shoulder, others that cinched the living and the dead arm-to-arm and thigh-to-thigh. Tom Harkin’s chin draped over her father’s right shoulder, like a friend whispering something in his ear. His arms trailed down along her father’s side, and when her father struggled up to his feet again, the dead man’s legs dangled in back, ready to kick him every step along the way.

“If a man robs his brother of all his tomorrows, then that man’s own tomorrows shall be spent carrying his brother in death as he failed to do in life.” Bloomfield snapped the book closed and looked at the ground as if he wanted to water it with tears. Melody knew he wouldn’t, not ever. He composed himself and gave her father the stern face again.

“Have you got anything to say, Grady?” She watched her father adjust to the weight. He had to lean forward to keep himself balanced, like someone with a heavy backpack. A load he could never take off. If it came off at all, it would be because it fell apart, piece by piece, and that could take a long time.

“I don’t guess ‘I’m sorry’ does any good now, does it?” her father said loudly, looking ten years older in just two days. The bones of his face jutted sharply over his thin beard. His eyes were a pair of darkened hollows as he sought out Jenna Harkin, who mirrored him, looking more like his daughter in this moment than Melody figured she herself did. “But sorry I am. Sorry I took your father from you. Sorry I can’t make amends for that in a way that would do you any good. Sorry that what I’ve done has left you to the mercies of these degenerate sons of bitches standing around looking—”

He cut himself off and couldn’t continue, because some things were just too painful to say. Especially when you weren’t saying them half so much about the orphan girl as you were about your own daughter.

Melody figured she could fill in the rest and get it right enough: these degenerate sons of bitches standing around looking at you, smacking their lips like they’re the wolves and you’re the deer.

As long as a man didn’t go too far too fast, he could get away with a lot with a girl who didn’t have a father around to protect her, no matter how she felt about his attentions. It was the way of things. Not with everybody, not even with most, but there were enough men who felt that way that it mattered, because there was strength in numbers and nobody wanted to give them cause to leave the village. Or worse, turn against it. As long as they didn’t draw blood and kept things mostly out of sight, it was best to let them have their way. People were content to pretend it wasn’t happening.

They had more in common than ever now, she and Jenna.

“I’m sorry myself, Grady,” and for the moment Bloomfield wasn’t the leader of the village council anymore, just her father’s friend. “Nobody could say you didn’t have a reason. But that doesn’t change the law.”

Could she and Jenna even still be friends, though? How could you manage to stay friends with the girl whose father had killed your dog for the meat? Jenna may have even eaten some herself, if she hadn’t known it was Patches. And how could she stay friends with you when your father had gone after hers with a chunk of firewood, maybe not meaning what happened next, but still, Tom Harkin was just as dead. How could the two of you go on like before, as if none of this had happened?

Now, finally, her father looked at her, Jeremy too, back and forth, up and down, and now she was glad she wasn’t crying. That would only make it worse, sending him out the gate with her tears on his conscience. She wanted him to see her tall, even though she wasn’t. Wanted him to see her brave, even if she wasn’t that either. The rest he had to know already.

“So go forth, Grady Banks,” Bloomfield said, “and carry the weight of your crime. Go forth, and carry the weight of the dead.”

Her father shuffled for the main gate in the village wall made of bricks and cinder blocks and the rusted hulks of what people in the World Ago used to call cars. One of the two massive doors creaked open to reveal the fields and forests beyond the gate and, in the distance, the raggedy men who lurked and dreamed, looking for a way in.

“It’s not necessarily a death sentence, you know,” said the man who’d eased up to her other side as soon as her father’s back was turned, opposite her baby brother, as though Jeremy didn’t count. Hunsicker, that was his name. He always stood like he was in a saddle, and had the littlest eyes she’d ever seen. The girls had a joke about him: he calls you “hon” and you just feel sicker.

“How do you figure that?” Melody asked.

“There’s been some that survived it. They didn’t catch nothing from the Rot that they couldn’t get over.”

“Yeah?” By now Jeremy was peering around from her other side, red faced and snuffle nosed and ready to grab on to anything that smelled like hope. She let his hand go and wrapped her arm around his head and pulled him against her and trusted she’d covered his ears. “Were they anybody you knew? You sat down and talked to them after they got to come back?”

Hunsicker worked his tongue inside one cheek. “It was a little before my time. But they say it’s happened.”

“Yeah, well, they say there’s been men that have walked on the moon, too, but do you believe that?”

His eyes got so narrow they almost vanished and he seemed to bristle, and even though she didn’t want to, she imagined what the weight of him had to feel like, and the smell of him under his clothes. Then his face relaxed again and he reached out to twirl a lock of her coal-black hair around his finger, and when it started to tug tight against her scalp, he gave it one last yank and let it go.

“You keep the faith, little sister,” he said. “And if there’s anything you need . . .”

She told him he’d be the first to know, because that’s what you did. You didn’t outright tell them no and make them mad enough to think they had to teach you a lesson in manners and being neighborly.

Then her heart seemed to stop awhile, and plunge from her chest through to the bottom of her belly as she watched her father struggle through the gate, but really, from behind, all anyone could see was more corpse than living man, until the gate closed and there was nothing to see at all.

Melody ran for the wall, dragging Jeremy at her side. He stumbled along to keep up, blind with tears and the back of his free hand smearing everything across his face. When she got to the north wall watchtower, the one her grandfather manned, she told Jeremy to stay at the bottom and not move, then she raced up the steps made of logs shaved flat, up and around again, like a square spiral, until she stood at the top platform, looking down on the fields and forests, and her father trudging resolutely in between.

He was headed for the tree line, every step as ponderous as if he carried on his shoulders not just the weight of a dead man, but the weight of a dead world.

She watched him go by, as slow a passage as the midday sun across the sky, until he was headed away from her again, and all she could see was Tom Harkin’s livid back and slack limbs. Once they got far enough away, weaving between the first spindly trees of the woods, it seemed as if the dead man was floating, and she supposed that was true enough, because now he was a ghost that would probably haunt her father to his grave.

Over the past two days, she’d learned all there was to know about the punishment known as the Rot, starting just after the men had showed up to detain her father for braining Tom Harkin. She’d feared what was coming even before the village council had rendered the judgment official.

The way her grandfather remembered, it had begun in the years after the Day the Sun Roared, and the World Ago shut down. Nothing ran anymore, he said. Three generations later you could still see the wooden crosses along the roads, at least the ones that hadn’t fallen down, many of them now green with plants that liked to climb, and some of them still dangling thick cables, like dead snakes. “Power lines,” he called them, and they’d fed just about everything.

Except one day they stopped working. Everything that ran on them stopped working too. Even everything that didn’t feed off the lines but ran the same way, like the cars, all that stopped working too. “Fried,” they called it. Everything had fried. All because the sun had had an angry day.

“Back then,” her grandfather explained, “everything came from someplace else. Then all of a sudden there was no moving anything anywhere, if you couldn’t move it on foot or by bicycle or with a horse.”

Melody had always had trouble imagining a world where there was that much to move, and how far it all had to go, at least until she’d seen pictures in books, but it was apparently a big deal. The way her grandfather told it, people used to go to war over big things, with big armies, and you always knew who was who, because the people who had to be killed were always far away, some godless people way over there, but now it was everybody going to war against everybody else, in a fight over what was left because there was no more coming.

They died in numbers so big she couldn’t imagine why you’d ever need to count that high. They died in such quantities that people got so sick of killing they’d do almost anything not to have to, except when they had no choice, or when they forgot.

Most, anyway. There were always the ones who still didn’t mind the deed, and never would.

And when it happened, however it happened, it was a problem. You couldn’t just let a murder go, because if there was no paying for it, that was like saying go ahead, do it again, we won’t stop you.

But coming right out and killing the killer? Nobody had the stomach for it, to be the one to wield the gun or knife or noose. It wasn’t like killing a deer, or putting down a crippled horse. Nobody was going to eat a murderer. It hadn’t come to that.

But there were no jails, either, not when people lived as nomads, survivors who’d gathered into tribes and kept on the move to scavenge what they could before moving along. They hadn’t learned to settle again in those days; hadn’t learned to stay in one place and grow and make what they needed and stop depending on people from way far away to send it.

Melody wondered who’d been the one to think up a punishment like the Rot. Who could’ve been that cruel, that wise? Someone had realized it didn’t matter if nomads had no jails, not when the killer had made his own, a prison he could carry with him.

That first night, when she’d finally fallen asleep after they’d taken her father away and cuffed him to the Thieves Pole—all the punishment the village needed, since stealing was normally as bad as it ever got—she dreamed of what she’d just learned. She’d dropped him back in time into those early days, a dead body chained across his shoulders like a deer carcass carried from the woods as he trudged along after the tribe, downwind, up and down the rolling hills and over the fields and across the crumbled scabs of the old black roads, barely in sight of them, barely able to keep up, and forced to spend the night alone as he stared in longing at the distant fires of their camp, never quite able to sleep as he lay with the corpse and listened for the feral dogs and other predators who’d come to fight him for it, and he would gladly have let them have it, if only he could.

But that was then and this was now.

Now he’d stick to the woods, she supposed. No need to travel.

More time to just sit and think of all the ways things might have gone differently.

She was determined to visit him in the early days of it, as often as she could. Family was allowed, and somebody had to take food out anyway, although the guards at the gate would always search her first, to make sure she wasn’t carrying any tools capable of cutting through leather and chains. Which stopped making sense to her almost as soon as it started. She wouldn’t need to sneak a tool out with her, just toss it over the wall somewhere private and fetch it later.

Sometimes it seemed the men around here weren’t half as smart as she was.

Still, if they were to find Tom Harkin cut free and rotting all by himself, they would know who’d helped, and she’d be even more of an outcast than her father was now, because the banishing would be permanent. She’d have no home here anymore, so the two of them would have to run off, and the world wasn’t a safe place for a man alone with an almost fourteen-year-old daughter. He’d never allow it. Never condemn Jeremy to that kind of life either, or to never seeing his big sister again.

She would stop at the woods’ edge, calling until he heard her, then called back so she could follow the sound of his voice.

She got used to it soon enough, the sight of Tom Harkin strapped to his back, pale here, purple there, blotchy everywhere else. His corpse wore dirty undershorts and nothing else, which somehow seemed more undignified than buck naked. Flies buzzed around the pair of red, crusty-dry, chewed-up-looking wounds on his skull. By her second visit, though, there seemed to be more of him than before, and his arms and legs seemed to jut where before they’d only dangled.

“Why is that?” she asked.

“Because he’s swelling up. It’s the gasses inside him,” her father said. His hair was lank and greasy, and he kept pushing it behind his ears. “You’ve seen dead animals puffed up out here in the woods, you know it happens.”

“Oh,” she said. “I didn’t think it happened to people too. That doesn’t seem fair.”

“We’re animals same as the rest.”

She looked him over, Tom Harkin like a giant, stretched-out waterskin grafted to her father’s back. He still didn’t smell so bad that she minded it, but then, it was October, which might have seemed like a blessing, the cool days and chilly nights helping to preserve the body. But everybody she’d talked to had concluded that this was just a subtler form of punishment. It made the ordeal last longer. Better, some thought, to have this happen at the height of summer, and get it over with quicker.

“Will he just fart it out?” she asked.

He looked her in the eye a moment, and immediately she knew, no, it wasn’t that easy. Nothing about this was that easy. “You shouldn’t hear about this.”

“I want to know.”

“I’m going to have to poke him soon. Through the side of the belly. I’ve just been trying to work up nerve to do it.”

“Poke him with what? Do you need me to sneak you a knife?”

“No, don’t get yourself mixed up in my troubles any more than you already are.” He turned, a cumbersome move, and pointed deeper into the woods. “I found a tree that fell not long ago, trunk still green, all split apart. There’s a long, jagged shank sticking out level with the ground, and I worked on it with a rock to sharpen it up more. That should do.”

She imagined him jogging sideways, building up enough speed to ram Tom Harkin sideways onto this skewer. He must have noticed the look on her face.

“If I don’t, Tom’s apt to swell up until he bursts on his own, and that’ll be worse. It’s the only way to ease off the pressure.”

She nodded, solemn. That’s when the ugly part of all this would truly begin. That’s when Tom Harkin would start turning inside out. That’s when the Rot would really take hold.

“Somebody told me this didn’t have to mean a death sentence. That there’s been some people survive it,” she said.

“Who told you that?”

“Daniel Hunsicker,” she said, then instantly wished she hadn’t.

“You stay clear of him, promise me.” Her father looked like he could boil water just by staring at it. “Him and any of that trash he hangs out with. Anything he thinks he’s got to say to you, you tell him to come out and find me and say it to this ugly head looking over my shoulder, and we’ll see how it goes from there.”

“Daddy,” she said sharply.

“Well, what are they going to do, tie another corpse on the front of me?”

“I promise, okay? I promise. Anyway, what he said, about it not having to be a death sentence, I didn’t believe it at first. But then I got to talking to Miles McGee. You know how he is about books. He’s worse than me, even.”

“As if such a thing was possible,” her father said, and sounded like his old warm self.

Miles McGee was a year older than she was, and most of his life had been the closest thing she had to a big brother, although now he was starting to look at her differently. Which she liked and didn’t like, at the same time. Wanting things to stay the way they were, knowing nothing ever did.

“Miles has this book he says came from that sheriff building some of them explored a couple years ago. Not a book, exactly, but a manual? I guess they had to keep it handy after the Day the Sun Roared. It’s about how to deal with a bunch of dead people after a disaster. It says you don’t have to hurry up and bury everybody in a big grave, because dead bodies don’t actually spread disease. People think they do, but they don’t.”

It was the one thing that genuinely felt like betting their hopes on, and Melody watched her father’s face to see how he reacted. If this news was as amazing as it sounded. For a while he just watched a beetle trundling across the forest floor, slow slow slow, like it wasn’t going to get wherever it had to be before winter came on.

“This is different,” he finally said. “No matter how careful you try to move with something like this on you . . . these straps, they rub you raw. Right through the shirt, they rub you raw. It makes it easy for an infection to get started. Do you get what I’m saying?”

“I . . . I don’t know.”

“It poisons the blood. Now do you understand?”

There was no good answer to this, so she just held herself tight.

“It means don’t get your hopes up. It means every time you come out here, we’ve got to treat it like it’s the last. Because there’s probably going to come a day when you’re going to stand at the edge of these woods and call for me and I’m not going to answer. Maybe it’s because I can’t. Or I don’t want you to see what it’s come to. Or it’s because while I still could, I went too deep into the woods to hear you. You’ve got to be ready for that, do you understand?”

Under her sweater, she pinched the thin skin of her belly hard enough to leave a bruise, because it was easier to deal with that than trying to imagine such a day. It was easier to stop herself from crying over the one thing than it was the other.

He seemed at peace now, resigned to whatever might happen, and in these moments when it was quiet, she would listen and wonder what her father heard in the night. If anything. Maybe he was too old to hear it, or not yet old enough. Maybe she was too, even at not quite fourteen. But there were those who said the woods whispered, or something inside them did, something that only the very young or the very old seemed able to hear.

And maybe those closest to death.

“I’m going to help you,” she said. “Somehow, I will.”

“I heard that Linda Gallenkamp’s dog is about to have pups,” he said. “Why don’t you check with her about taking one off her hands?”

Was he not even paying attention? “I don’t want one of Linda’s pups. I want Patches back.”

“I know.”

“Just like I want you back. And if I can’t have Patches, I’ll settle for you.” She stopped and, in spite of everything, had to laugh, because so did he. “That didn’t come out right.”

“Not much ever does,” he said, then seemed to wish he could take it back.

“I’m going to help,” she insisted again, and that settled it.

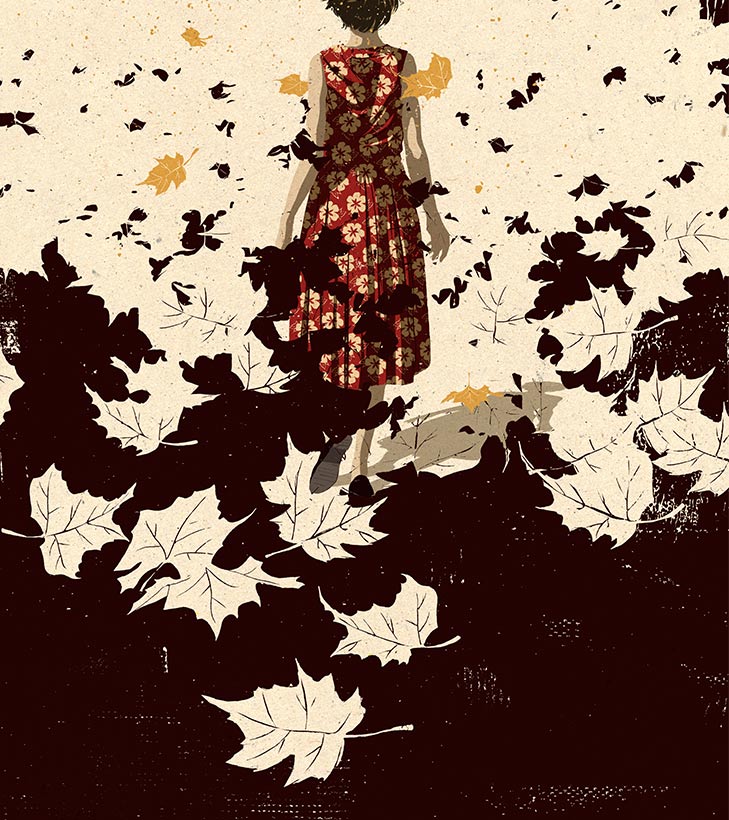

When it was time to go, she wasn’t ready to give up the woods yet, because she wanted her own time to pause and listen. She took the long way home, keeping inside the trees deep enough that she couldn’t see the back wall of the village, still plenty of leaves on the limbs in the way. They no longer blazed with the colors she loved best, though. All the reds and oranges and yellows were muted now, and dull. Even the woods felt like they were dying.

Might as well start wishing for spring, and green. It seemed the only good thing she could count on, if only it weren’t so far away.

There were the in-between times, too. In between visits, between sleep, between chores, between distractions. That was when Miles McGee found her on the third day, which was just like him—more often than not, he knew right when to show up. He caught her after her turn cleaning out the poultry houses, when she was amenable to most anything that would stall her from going back to what she vowed would only be a temporary home. Which wasn’t all that different from the coops, either, because her grandmother could cluck as bad as the hens.

“Here, I’ve got something for you,” Miles said, and gave her a rectangle of metal and plastic that fit in her hand. “What’s this one, can you tell?”

She looked it over. “I think it’s another one of those music-player things.” It said iPod on the back, on the metal, and she had two of these already, although none of them looked exactly the same. “It’s been two weeks since the last scavenge—where’d you get it?”

“Found it while I was picking corn this morning in the outer field. My guess is one of the raggedy men dropped it while he was stealing a few ears in the night.” Miles spared a contemptuous glance west, in the direction of the cornfield, and beyond it, the raggedies. “Or maybe it was his idea of a trade.”

Everyone hated the raggedies, and Melody supposed she did too, but sometimes she felt she ought to think better of them, because after all, her own family and everybody else here had come from people who were once more like them than not. They must’ve been raggedy too, at one point. They’d just had the good sense to stop here and dig in and call it home.

Strange, though, to think that one of them out there could be so like her now, if this contraption in her hand was any indication. He had to have carried it around in spite of everyone else thinking it was useless junk. Maybe it gave him hope.

“Anyway, now it’s yours,” Miles said.

She thanked him and had to strain to look him in the eye. He was either too tall for his hips or too skinny for his height, one or the other, and crowned by a mop of curly hair she would’ve given anything, except family, to have on her own head. He knew it, too. Maybe sprouting from her children would be almost as good, and that was what he was counting on.

He tapped the gadget in her hand. “The day you do get one of these things working, I really hope I’m here to see it.”

“Then don’t run off a-scavenging every chance you get,” she told him, her voice lighter than she felt, or maybe for the moment she felt lighter than she realized. Then she headed for home.

The village scavenged once a month or so, volunteers taking to horseback and bringing home whatever they could of the World Ago that could still be of use after all this time. Some liked these trips for the excitement of discovery, others for the chance to get away and see something different. Some, like Miles, wanted to keep going; others saw enough to satisfy them for the rest of their lives.

They plotted their destinations from an old map of what used to be the state the land was once part of. Where they’d scavenged already was like a growing ring around the village, and Melody found it sad to think that there would come a time when they ran out of places to go. What was left would be too distant, keep them away for too many days at a time. There would come a point when they’d picked it all clean, like crows on carrion, leaving nothing but bones.

Melody had gone twice since her father considered her old enough for the rigors of such a trip, and ever since the first one, she’d never looked at the future the same way again.

What drove them out time and again was the belief that you could never have too many farm tools, or too many jars and plates. Sometimes, if it had been stored well, even clothing had survived the decades. This was all fine, but what had captured her imagination were the tools that were of no use to anyone, not since the Day the Sun Roared, because these were the ones it had fried.

By now she had watches that had no way of winding them. Things that played music from your pocket, windows that played pictures in your hand. Thick wands that people used to point at contraptions across the room, and control them. She had a few of the phones they used for talking with people no matter how far away they were, and a couple of the flat slabs that had been called computers and apparently did so much that they ran the world. Until they’d fried.

She’d collected what she could during the scavenging trips she had joined, and Miles and a couple others were diligent about bringing her anything that looked interesting, whatever they were able to carry that wouldn’t interfere with what everyone else considered important.

Books, too, she craved, and Miles was a champ there because he brought her plenty of those as well, and shared what he’d kept for himself. Sometimes it all went together: if there was anything she was determined to do, besides be good and do her chores and not give her father reasons to have the frets, she was resolved to figure out this whole electricity mystery and get something running again.

Sometimes she took the devices apart and couldn’t get them back together again. Other times she cleaned them up, inside and out, so good they looked new, and you’d almost expect one to turn on by itself if you just stared at it hard enough. Except they didn’t have batteries, so she hunted down how to make her own, with small jars and strips of copper and nails and some of the cider vinegar they made from apples. She’d open up some of the gadgets and run wires from the battery to different spots inside them, and a few times coaxed a pale flicker of light across the screens of a couple of them, and once a burst of numbers, but nothing more, although it gave her hope.

It was something she didn’t mind doing in front of her father, because he saw no harm in it, and would sometimes smile as he watched her tinker with this and that. But that was in their own trailer, and now that her father had forgotten not to kill, and she and Jeremy were staying with the parents of the mother she didn’t much remember by now, it was different.

“What’s that you’ve got there?” her grandmother asked that afternoon while watching her scrub at this latest gift from Miles.

Melody told her, and showed her a few of the other gadgets that seemed to have promise. And wondered for the hundredth time why she and Jeremy had had to come here; why their grandmother couldn’t have packed a bag and stayed with them in their own home. It was like ordering them to surrender all hope from the very beginning.

Her grandmother frowned at the ancient iPod, looking not nearly as indulgent as her father usually did. Her lips seemed to disappear. “Foolishness. You’ll never get any of that working. It’s just old junk not worth the bother of carrying around.”

Melody pointed at a switch on the wall that didn’t do anything and never had. “Wouldn’t it be nice to have lights like they had in the books? You just jiggle that thing and there it is? You wouldn’t like that?”

Her grandmother made a sour-apple face. “What could a light like that show me that a good candle or lantern doesn’t already? There’s nothing there that’s any different.” She shook her head no, a thousand times no, then jabbed a finger at the old dead iPod. “You just leave that alone, if you know what’s good for you. That junk there, that’s how it all starts.”

“How what all starts?”

“You don’t remember the things your grandfather and I do, from when we were little, before the sun set everything right again. You can’t remember, because you weren’t there. So don’t tell me you want to go back to a world you never even belonged to. It was a sick and decadent world back there, and I’m amazed the sun let it go on as long as it did. But it’s over now, and there’s no need to insult the sun by trying to bring all that back.”

“What was so wrong with it?”

She flustered along as if asking where she could possibly begin. “If I was to get started on that, we’d be at it all day, and I still don’t think I could get it across to you in a way you’d accept. Not when your mind’s already made up that there was something better about it.”

“Oh,” Melody said. “I had to be there, right?”

“That’s it exactly. You had to be there.”

And you weren’t, Melody decided. You don’t really remember anything at all. You only pretend to because you never want anything to change.

This made sense, once she thought it through. She didn’t know by how many years, exactly, but her grandmother was a few younger than her grandfather. And he was barely able to remember the World Ago.

“I notice you’re okay with living in this trailer,” Melody said. “If everything from back then was so bad, how come we’re not in a log cabin?”

“The mouth on you,” her grandmother said with a huff and a sigh, but, too, she was grinning a little, until she wasn’t. “Just you watch yourself, playing around with that old junk. Be careful who sees you do it. Most people around here are happy with things the way they are. They won’t want to see the likes of you getting out of hand and forgetting your place.”

“My place? What is my place?” It was worth asking, even if she couldn’t imagine any answer that wouldn’t dismay her, and possibly horrify her.

Her grandmother wouldn’t look at her now, or wasn’t able to say more, and Melody took that as an answer anyway, maybe the worst of all, because her grandmother wasn’t a woman to hold back her opinion on anything.

She decided, just the same, that maybe she’d better take the gadgets back home, to her real home, and find a better hiding spot for them.

She planned to join her grandfather on the northern watchtower that night, and thought she’d do it alone, except she’d only crept six steps from her bed when Jeremy roused and demanded to know where she was going. This was something new, this refusal of his to sleep unless she was nearby. She couldn’t even sneak away once he was down. It was as if he had a field around him that just knew.

“Take me with you,” he said, small and insistent, his hair sticking every which way hair could stick.

“It’s cold out,” she whispered. “We won’t be out but a minute or two before you’ll be whining to come back here, and I’ve got to see Grandpa longer than that.”

“No, I won’t! I’ll stay as long as you do!”

She scowled and shushed him. “You’ll wake Grandma.”

“So what if I do, it’s your fault.”

“Then get yourself dressed, and get it done before I count to a hundred, because once I do, I’m out the door with or without you.”

He actually needed to 112, but for Jeremy that was still pretty good, then they slipped out into the dark of night, creeping through and around the scattering of homes and kitchen gardens between their grandparents’ place and the northern tower. As soon as they ascended to the top platform, Jeremy curled up on the wood planks next to the cast-iron stove and, bathed in the radiant heat of the fire burning hidden within, promptly dropped back to sleep.

Her grandfather gazed fondly down at the boy, then shifted on his chair and drew his blanket around his shoulders and resumed his vigil with the night. Near his head hung a bell he’d never rung, at least not for anything to do with the raggedy men.

“Have they ever attacked?” she asked. “Ever once even looked like it?”

“Nope,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean they won’t tonight, or the next.”

“Why don’t they?” she asked, and wondered if even now, out there far beyond the gate, they were watching, scheming. There were raggedy women too, she thought, had to be, but once someone got raggedy enough it was hard to tell exactly what they were underneath.

“It doesn’t matter how much someone wants to take what you’ve got,” he said. “Most, if they’re not willing to pay with their lives for it, about all they’ll do is look and grumble.”

“Has anybody ever tried to run them off?”

“Many a time. They just scatter. They’re gone before you ever get there. And then, before long, they’re back again.”

“Why not just kill them? It doesn’t seem like it’d be hard to pick them off with a rifle. They’re not us.”

“We’re still better than that. Or we say we are. Maybe if we repeat it often enough it’ll even be true someday.”

“I’d get bored. If I was them, I’d’ve gotten bored a long time ago and gone home.”

Her grandfather made a humming sound in his throat. “The way they look at it, I’m sure they think they are home.”

Manning the tower was a good job for him, because his eyes were still sharp, and he said he didn’t need much sleep anymore, and anyway, her grandmother snored even if she would deny it with her dying breath, so it was the best way for him to enjoy some peace and quiet at night.

“Do you ever hear them, out there?”

“Not much, and not very often.”

“What about from the other directions?”

“From the woods, you mean?” He sounded perplexed. “No, they don’t seem to creep around that direction, not that anyone’s ever noticed.”

“I don’t mean hearing the raggedies so much as hearing . . . anything.”

He turned to her, and she imagined his eyes had gone narrow, the way they did when there was more to say and they both knew it. “Anything covers a lot, sweet pea. What are you getting at?”

She told him about the whispers in the woods that seemed only for the ears of the very young and the old. He had to have heard about it, at least. A thing like that couldn’t have just been a story kids told each other. If there actually were such a thing as kids anymore.

“So you’re saying I’m old, then.”

“Sorry.”

“I don’t feel old.” He stared east, into the black of the forest night. “Maybe because my ears are pretty good too, same as my eyes. Yeah, you can hear things from out there and not always know what they are. Now, you get a fox squabbling with a raccoon, you know what that is. But other things? They’re not so clear and maybe they do sound like words sometimes.”

“What do you think it is?”

He chewed on that awhile, then looked at Jeremy, still curled in sleep, as his lips murmured something that made it sound like he wasn’t having any fun, wherever he thought he was. Melody reached down to stroke his shoulder, and he settled.

“Maybe it’s like that,” her grandfather said. “Maybe the woods are dreaming.”

She liked the sound of this, even if it made no sense to her. “What could they have to dream of?”

“All their tomorrows and forevers, maybe. And what we are to them now, instead of what we used to be.”

She’d never heard him talk this way, but then, she’d never asked. “What was that?”

“That part of the world, we used to think we were its masters. Maybe we were, maybe we weren’t, but now we for sure aren’t. All we can do is build a wall around a bunch of houses and trailers and one of our fields, and hope that too much of the rest doesn’t creep in, and stays out there with your raggedy men. And as for what we are to it all now . . . I couldn’t even begin to guess.”

Now she started to reconsider. Maybe she didn’t like the sound of this after all. She’d spent most of her years thinking that her father knew everything there was that was important enough to know, but he hadn’t even known enough to not forget about not killing. And if her grandfather didn’t either, the world seemed like a bigger place, darker and more unknowable than it had seemed already.

“There was a girl I once knew,” he went on. “This was before I took up with your grandmother, so it really was way back. Tara . . . that was her name. She was another one like me, just old enough to remember what it was like before the Day the Sun Roared. So she knew what things were like before, enough to compare. She had herself some strange ideas.”

He’d loved her—Melody could hear it in his voice, every word. By now she remembered less and less about her mother, who’d died bringing Jeremy into the world, mostly fading moments, and she always wished she could remember more about the kind of woman who would’ve named her daughter Melody. And now, from the tone of her grandfather’s voice, she wished she could’ve known this Tara woman too.

“She had this idea that there was something alive about the world, especially in places like the woods and the prairies and mountains and rivers, and that it was barely hanging on by a thread when the sun had its day. And that after the power lines went dead, we lost hold of those chains and shackles we’d had on the earth, so it was going to start to come back.”

“Do you believe that?”

“I couldn’t say. But nothing I’ve seen since convinces me she was wrong.”

“What happened to her?”

He took some time to prepare himself for this one. Finally, “She was okay as long as we were roaming. But once this place started coming together . . .” He pointed into the darkness. “She said it called to her. That spot over there at the edge of the north field, where you’ve been going in to meet with your dad? She went in about there. Never came out again.” He seemed to have forgotten his arm was still pointing, hanging in the air until he remembered to put it down again. “Not a week goes by that I don’t expect her to step out again, same as she was then, like nothing’s changed.”

“What would you do if she did?”

This made him laugh. “Ask if she could even recognize who I am anymore.”

He seemed to not want to say anything for a while, so she shared the silence with him, and soothed Jeremy when he needed it. They watched the night beneath the moon and the river of stars, the night in all its shades of darkness, and she’d never known there were so many. But then, she’d never watched like this before.

“See that?” he finally said, pointing in the direction of the woods, only higher, not at the trees, but above them.

It was a light, dim, and where it came from, she didn’t know, but it lingered and grew until it seemed as bright as a lantern, only colder, a cold and fuzzy light. It bobbed along for a bit before she noticed a few others scattered across the horizon, and then the first one sank beyond sight amid the trees. They roved like fireflies in the summer meadows until, one by one, they too drifted out of sight.

“What were they?” she asked.

“How should I know?” her grandfather said. “But my guess is, something you never would’ve seen before the whispers started.”

Tears, she thought after staring at them for a time. That was what they were. Tears of light, falling against the endless void of darkness, with no telling who or what was capable of shedding them.

Here in the village, they had a saying she’d been hearing ever since she could remember: Out of the death of the old, arises the new. It had always made sense before, because people seemed to use it like they were talking about the civilizations of then and now . . . if in fact civilization was really what they had here.

The saying didn’t have to be wrong, but maybe it was a lot more right than anyone realized, because it also referred to the soul of the world, and what was now possible in it, and everything that was most real and true.

Soon came the day that when she saw her father, it was so much worse than the time before, she was surprised he was still letting her see him at all. It wasn’t a man on his back anymore. It was past that, past time for thinking of Tom Harkin as a man, even a dead man. He was just a thing now, a putrid thing that hung in and out of his skin and fouled the air around him, along with every part of her father that he touched and smeared and leaked on.

“What’s that you’ve got in your sack?” he asked. His voice was weaker, and his eyes were pinkish, the skin beneath them like puffy red half-moons.

“Nothing much,” she said. “Just some stuff I’m taking into the woods.”

“It looks heavy.”

Seeing him now, it was the first time she had a truly bad feeling about all this since the start of it, and she’d accepted not just what was happening, but the chance for hope. Hope, on its own, didn’t have to smell what she was smelling. She inched closer to where her father was half lying, half squatting before a tree, then realized with a jolt that he’d been using the tree to rub against, like a bear with an itchy back, grinding Tom Harkin away a layer at a time.

“Daddy . . . ?” She reached out to touch his cheek, and it felt as hot as the iron griddle on the wood stove. “Are you going to be okay a little longer?”

He shut his eyes. A thick tear pearled in one corner. “An animal was eating on him last night. I don’t know what. Nothing very big, but I could feel it tugging pretty hard. I couldn’t move. All I could think of was . . . was how was it going to know where Tom ends and I begin.”

She wouldn’t cry. She would not cry.

“I’m not even sure myself anymore.” Her father’s voice started to break too. “He talks to me now. I know he can’t. I know that. But that doesn’t shut him up.”

“Yeah?” She had no idea whether it was better to humor her father or set him straight. “What does he have to say?”

“I don’t have the heart to tell you,” he said, but she must’ve glared at him severely enough for bringing it up in the first place that he relented. “He says he’ll see me soon. He says we’ll be roaming these woods forever, him and me.”

She sneered at the very idea. “He always was more liar than not.”

Melody scowled at the ghastly head bobbling over her father’s shoulder, its eyes a couple of milky-looking plums and its rotten-breathed mouth open like a cross between a landed fish and a drooling idiot. Would it be cheating if she went back for a knife and cut the head from its neck? Maybe that would quiet him down to her father’s content. Maybe give Daddy something to do, too, like find a hole and throw the ignorant head into it, along with its hateful ideas.

“How’s Jeremy?” he asked.

“Ready to see you again.”

She said it with hope, like there was no doubt in the world this would happen, but it clearly gave her father a pain to hear it.

“Does he even understand one bit of this?”

“He understands dead, enough. He just doesn’t want to have to understand it for you.”

“Tell him . . .” her father said, then drifted off, all puffy red eyes and skin like sweating cheese. “Tell him I’ve gone to go find your mom, and it’s got to be one or the other. Tell him there’s no going back and forth.”

“If it comes to that,” she said, and grabbed her sack, and before she left she kissed her father on his feverish cheek, the side opposite the rotting head, so it wouldn’t feel so much like they were being watched. She let it linger, so he would remember it awhile longer, and maybe the act would be enough to sustain him another day.

There were no maps for this, nor anything in any book she’d ever opened, but then, even if she had every book from the World Ago stacked in front of her, she doubted there would be a line in any of them to advise her when she’d gone far enough. Those had all been written for one world, and this was another.

She’d walked and she’d walked, shifting the heavy sack from one arm to the other, and her feet had crunched so many brittle leaves that she no longer heard them, and now, finally, it felt right to stop. It just did. She had to trust that.

Women knew things, knew them without knowing quite how—they just did. Which scared the men sometimes, some of them, so that had to be a good thing. They looked at her like she was a woman now, and that part of it didn’t feel so good, but maybe the time had come to own it anyway, if it meant she would know things too.

It was a stump she’d found, all on her own, as big around as a barrel and leveled across the top from some ancient meeting with a saw. Long enough ago for the wood to look soft and welcoming, with scabs of lichen and a beard of green moss. It was a table now, one more example of the new rising up from the death of the old.

Melody opened her sack and pulled out the first thing to fill her hand, a phone that hadn’t carried a voice for decades, and she set it in the middle of the stump. She groped in the bag for the one thing that, more than any other, made it so heavy, and came out with a rock the size of a flattened potato. At first she’d thought to use a brick for this, but no, what if they didn’t like that—the square edges of it, the man-madeness of it. The stone was rounded and smooth, as only a river could leave it. They would know what it was.

She held the stone high, then brought it down on the phone, and it hurt almost as much as if she’d smashed her own hand.

“Do you see this?” she called out to whatever would listen. “This is for you! They call it a sacrifice.”

She loaded up another one from the bag—a camera, she thought it was called—and it came apart into more pieces than she would ever know how to put back together.

“These mean something to me! But I figure you’d be just as happy if they never work again. The way my grandpa talks, every one of them was like another link in the chains that held you down.”

Melody pulverized another that was nearly all window, until fragments of green plastic rattled out of its mangled shell. It hadn’t even mattered that it never worked—this one just felt especially good under her fingers.

“Maybe that’s true and maybe it isn’t, but either way, they still mean a lot to me.” Her chest was hitching with the refusal to cry at the surrender of it all. “But I’m giving them to you. If it’s your world now, then maybe you’ll like them this way better. There’s still one thing I love more than these, and what they mean, and I don’t want to have to give my father up. I don’t want to see him follow that asshole Tom Harkin into the earth too. Not if there’s the least chance.”

She battered and she smashed, and despite the perfectly good reasons for it, still, it felt like killing some better future before she’d had a chance to enjoy even the tiniest taste of it.

“All you’ve got to do is spare my daddy from the Rot,” she begged whatever might have paused to hear. “Because he’s got to protect me. I need him between me and those other men, and he’s all I’ve got that can do it. All you’ve got to do is help him keep well enough to live through this. The . . . the microbes in him, they’re more a part of your world than ours. Tell them to leave him alone. They’ll listen. They have to listen . . .”

It had never seemed any clearer than it did now: the people and the forces that meant to destroy would always win, always come out on top over the ones that wanted to build. The world and everything in it was just geared that way, made to fail, made to fall. The most you could do was draw your line in the dirt and hunker down behind it and keep the worst on the other side of the line where it belonged, and try your best to stop it from crossing over for one more day.

She smashed until her sack was empty and there was nothing left, then she took handfuls of pieces that were still on the stump and threw them into the air and let them fall where they may. Then she sat down in the middle of them and screamed until her lungs ached, and shucked her sweater to go bare armed, and used a piece of the rubble to scratch at her skin because she remembered a story about some man that God was tormenting who sat around scraping himself with a chunk of broken pottery. It had turned out all right for him in the end. Do a thing like that, and they had to know you were sincere.

Then that drama, too, played itself out, and she had no idea how long she’d stayed out here, just knew that the sun was nowhere near where it had been when she’d started. Treetops swayed and leaves rustled and birds called in the distance and the blood dried and she was spent, utterly spent, and doubted she could stand and run even if a bear ambled up and mistook her for lunch.

She might not even much mind.

Maybe this was how prayers got answered now. The bad still happened, but the Powers’ idea of kindness was hollowing you out so you didn’t feel it anymore.

And when, at last, she heard the footsteps, she thought there it was, the bear, right on cue . . . but on second thought it seemed like any bear worth his teeth would either be a lot louder or a lot quieter. You’d hear him coming a mile away or never hear him at all. These were just footsteps, and not even quite right. More like the idea of footsteps that someone was putting in her mind.

Because, if you were all kinds of wise, that’s what you’d do to set a girl at ease when you came up on her, and there was something about you that wasn’t quite human, and not animal, vegetable, or mineral, either.

Melody peered up at her from the forest floor, afraid to blink. There was something about the woman, if a woman this truly was, that wasn’t wholly there, yet was more there than just there. Like stained glass, Melody decided after a few moments. She’d been in a church before, on the scavenging trips, a real church from the World Ago. It had been a sunny day, and she’d never seen such brilliant colors in her life. Saints and shepherds, green grass and blue skies, even the reddest fires of Hell, lit by the shining sun . . . yet she knew one flung rock could put an end to any of them.

The delicate clarity was like that all over again, Melody and the sun and this woman-thing in between, either filtering some of the light through her or throwing off some of her own. Neither option was particularly comforting, when you got down to it.

“All right,” she said, looking Melody up and down, and the mess she’d made of herself. “If you want it this badly, all right.”

“Just . . . just like that?”

“It’s never just like that.”

Melody stared, because there was something about her that was familiar, even if she couldn’t say what or how or why. But she too was a woman now, Melody had to remind herself, and women knew things.

“Is your name Tara?” she asked. “Or did it used to be?”

But no, that wasn’t possible. How long had it been since her grandfather had watched his one true love walk into the woods and never come out again? That woman, she would’ve been young then, not much older than Melody was now. This woman, while she wasn’t as young as all that, wasn’t old, either.

“No, that couldn’t be,” Melody said. Still, the way her grandfather had spoken of Tara had made her seem so familiar. “That just . . . No.”

“If you knew enough to ask the question,” the woman said, “didn’t you really know the answer, too, already?”

It cut the tongue right out of her, as Melody sat up and scooted back to lean against the stump. Trying to make sense of everything that couldn’t be, but was. You hoped. You hoped for things, and pretended they might be within reach, and when they didn’t answer you could console yourself that, well, you’d tried.

But if they did, when they did . . .

This Tara, she was neither young nor old. She was just right. Like she’d grown into what was, for her, perfection, then decided to stay there. Her hair was red, the color of rhubarb, and nearly to her waist, thick as summer wheat. Her eyes, green. Clover would want to be that shade of green, if it only knew.

Men would love her, of course, and she would be the ruin of them.

That much, at least, was a comforting thought. As long as it was the right men.

“If it’s never ‘just like that,’ then what is it like?” Melody asked.

Tara said nothing at first, just let the question toss and dance on the winds, but then she got down to it and told her what was what, how these things really worked, and never once had Melody considered that everything she’d brought to sacrifice, and the blood that followed, was only the first step, just a way of getting their attention.

Melody thinking, No, come on, please, anything but that.

It was late when she got back to the village, but since it was October, late wasn’t what it used to be, and when the guards at the gate chastised her for it, she glared at them with all the spite she could muster until they backed down like whipped dogs. Some guards.

There was no hiding the state of her arms, and her grandmother made a fuss when she saw them. Without even having to think about it, Melody spun a lie of gravity and thorns. Grandmothers were always ready to believe the worst about clumsy girls. Jeremy, though, knew better. He might still believe the part about the thorns, but he looked at her as if he knew, absolutely knew, that something of huge importance had happened, and that he wanted her back the way she used to be.

“Did you see Dad?” he asked.

“Sure. He’s built himself a nice shelter.” Then she hugged him and held tight and kissed him on top of the head. “He said to give you that.”

When Jeremy tried to squirm away, like he always did at the four-second mark, she refused to let him go, because while he may have been a pest sometimes, he was her pest, and her responsibility too, and she’d almost been tempted out there in the woods, deeper than deep, to say, Yes, okay, if that’s what it takes, I’ll bring him to you, until she remembered everything about that bond their father had always made sure she would never forget.

She was the only big sister Jeremy would ever have. That counted for something.

And should have been enough to ride this dilemma through, until their father’s life or death was decided and there was no more need for her to choose. Would have been enough, if only she could have stayed inside.

Inside, where she wouldn’t have to notice the eyes that followed her, Hunsicker and his kind, the rough men who liked small things in their beds.

Inside, where she wouldn’t have to contend with the sight of Jenna Harkin, and how there seemed so much less of her now. So much less life, less hope, so much less left to look forward to in each and every tomorrow. So much less love between them. Fact was, she’d have to say Jenna probably hated her now, for her father’s crime, or would have hated her if she’d had that much fight left. Her eyes were downcast and resigned, staring at the ground as if she spent too many hours thinking of the day she’d be under it. Jenna was going dead a little at a time, whittled down to hips that moved on command and a mouth that told whatever lies it had to, when it wasn’t otherwise occupied, and the rest of her just not there anymore.

Wherever Melody had to go, she tried to walk lightly, with no shows of pride or promise. She walked as if there was even less to her than there was to begin with. She walked as if she had no breasts, small as they were. Walked as if she had no hips. She walked pretending that she didn’t reflect the light of the sun at all, invisible, just a dark, sexless smudge drifting across the ground.

It made no difference. Their hungry eyes found her anyway, and their blackened hearts filled in the rest.

“How’s he getting along out there by his lonesome?” Hunsicker asked her one afternoon, ten paces from the chicken coops, and she’d never seen him coming. He sounded like the happiest man on earth.

She stood her ground, though. He’d enjoy it all the more if he could get her backing away, just so he could keep dogging her. “He’s getting by, and he says anything you’ve got to say to me, you can run it past him first.”

When Hunsicker smiled, his tiny eyes twinkled. He’d not shaved in days, and the brown stubble looked coarse enough to grate nutmeg. If she’d let herself, she would’ve shuddered at the thought of the feel of it.

“Then maybe we’ll have us a parley, him and me. While there’s still time.” He looked her top to bottom, seeing everything, everything. “How much do you weigh, little sister?”

What kind of question was that? She had no idea how to answer, even if she’d known what the scales would tell.

“Because you don’t look like you’d weigh much more than a full feed bag. Such a bitty thing, someone could hang you up here off his shoulders and hardly know you were there at all.” He peered down his nose and gave two sharp sniffs. “Except for the smell.”

Then he laughed and went on his way.

She couldn’t live like this, and wouldn’t, not for long, and if everyone else in the village expected her to, then it would end the same as with her father, and she’d be the next one driven into the woods, dragging along a two-hundred-pound corpse chained to her back, Hunsicker’s or somebody else’s.

Whatever they were out there, awakening beyond the wild, they who could hear a girl’s tears and smell her blood and who demanded little boys, maybe they were kind, in their way.

Maybe they would be nice to him.

She wasn’t sure when they crossed it, but knew that at some point they’d taken a step that marked the farthest away from home Jeremy had ever strayed. He’d never been a-scavenging, only looked impatiently forward to the day when he would. He was on the adventure of his life now, and she couldn’t even tell him.

She led him by the hand the whole time, and he consented to it without a single complaint, not like him at all. But she knew why. It was a big world getting bigger all the time. There’d been a lot of walking since they’d heard the last faint sounds of the village behind them. To his eyes, she was sure, the trees looked taller, and the sky-eating clouds looked angrier, and the streams looked swifter, and the leaves underfoot crunched louder, with menace, calling out for bears and packs of feral dogs.

“Why would Dad be out this far?” he asked. “It’s too far. Nobody’d want to take him his food.”

“Because we’re not just visiting him, silly. We’re going away with him. He’s cut Tom Harkin off himself, so now we’re going to make a new home, just the three of us.”

Jeremy peered up at her, clomping along at her side and doing the calculations for all the massive change this would entail. “You mean we’re never going back?”

“Of course not.”

“Then why didn’t you tell me?” he bawled. “I would’ve brought some shirts. And I’m not even wearing my favorite pants. Or my digger! I’ll need my digger!”

“Now think,” she told him. “If anyone had seen you dragging that much stuff along, they would’ve known something was going on.” He balked, unable to walk and fret at the same time, so she yanked to keep him moving. “Dad’ll make you a new digger. And you can get pants anywhere.”

He would hate her forever, she feared. For everything, but most of all for the lies. Every last thing he was hearing from her, just one lie after another.

But then, she needed the practice. She still had no idea what to tell her father when he came back to the village, healthy and spared, the ordeal of the Rot behind him, crying and hugging her with relief, then looking for his son so he could hug him too.

When she found the stump again, it seemed like so much longer ago than yesterday that she’d been here last. She had him sit facing ahead, while she sat facing the direction they’d come from, the two of them back to back.

“You watch for him that way,” she told him, “and I’ll watch this way.”

He complained that he wanted them to face the same direction, complained because complaining was his job, it seemed, so she told him that this way they got to see twice as much. Nobody could sneak up on them, and they had each other’s backs. All lies, even the twice-as-much part, because it was all she could do to slump there and stare at the forest floor. She couldn’t even keep her head up, fighting against the weight of her decision.

How would they know, she wondered. How would they even know to come and collect their due? Did they have eyes everywhere, among the birds and snakes and fast-footed hares? Or were they listeners, instead, zeroing in on Jeremy as he chattered about what their new home might be like or the unrelieved pounding of her heart?

Or maybe they felt things in the wind that she herself would have no idea how to begin seeking, and could follow them to their source, the way a book she’d borrowed from Miles McGee told of fish called sharks, and how they could follow blood through leagues of ocean to the open wound that shed it.

“Are you cold?” Jeremy asked. “I can feel your back shaking.”

“No,” she said, so he wouldn’t turn around. It was an easy word to say, no matter how much your throat was clenching. Then, when she could, “Maybe a little.”

He scoffed. “It’s not that cold out.”

And he would hate her forever. Dad too, if he knew.

But they would be nice to him. Of course they would. There was a reason for this, the way there was a reason for everything. Tara, she was still fine, whatever she was now . . . and that was it, maybe. She’d never had a son of her own, and now she wanted one, although not just any boy would do. She could only be happy with a boy descended from the only mortal man she’d ever loved.

They’ll be good to him . . .

“Hey,” he said. She felt him straighten against her back. “I see someone moving. It’s got to be him, right? Got to be Dad.”

“Probably.” She clenched her teeth to make the rest of her mouth work. “But he’s been sick, remember. He may not look himself.”

. . . and one day he’ll be glad . . .

“No . . . no, I don’t think it’s him.”

“He’s got some new friends now, it might be one of them he sent to find us.”

“There’s more than one. They don’t look like anybody I’ve ever seen.” Jeremy made a sound he’d never made before and began to squirm. His bony little shoulder dug into her back as he twisted around. “You’re not even looking!”

“Just turn and face the way I told you to, Jeremy,” she snapped. “Don’t make me tell you again.”

She could hear him breathing, faster and heavier now, and when he made a whining noise, he sounded just like Patches did whenever he knew something was wrong but couldn’t grasp what.

“Why would Dad have friends like this?” Jeremy whispered. “There’s something wrong with these people . . .”

He began to say her name, over and over, “Melody Melody Melody,” sometimes a question and sometimes a plea. She heard the heels of his shoes drumming back against the stump, and gradually something else began to fade in beneath that, a sound like walking, almost, as if things that no longer made a noise were trying to remember how to do it, so they would seem normal.

They’ll be nice to him, and someday he’ll be glad.

“These aren’t really people, are they?” His voice had gone higher and tighter. “People don’t move like that.”

Okay, so they could still make some noise after all. They could still grunt. “You’re not looking, you’re not looking!” he cried, all accusations now, and he whirled on the stump, practically on top of her back, throwing both arms around her shoulders and burying his face against her neck, his breath scorching.

“You’ve got to go with them. You just do.” Her voice was barely there. “They’ll take you to where Dad is, and I have to stay here.”

But he knew, knew something was wrong but couldn’t understand what. Or why. At least Patches never wondered why, and this made it ten times worse. She kept her head down so she wouldn’t see any of it happen, then squeezed her eyes shut so she wouldn’t see the shadows. But she felt them, whatever they were, a presence, a pressure like waves of heat and hunger, as they gathered on either side of the stump, and while her brother squealed, they gently, very gently, peeled his arms free of her and lifted him away, and he was gone, the weight of him, the wet of him, just gone.

She wasn’t going to move, not as long as Jeremy was crying, not even to cover her ears, and he cried for a long time. The sound receded behind her as slow as ice melted, faint fainter faintest, his each and every wail yanking at her heart, ever more violently the farther away it got, until even the echo of him was gone, fading like a last wisp of smoke that dissipated among the trees. But at least it never cut off abruptly, and she supposed that this, too, was a good sign.

He died anyway.

Her father. Dead.

There was no body to find, but what other conclusion was she supposed to draw? She could take a hint. She was a woman now, and women knew things. She could feel it as surely as the coming winter: that hole in the world, in the shape of her father, turned permanent. He was never coming back to refill it.

And, within the village walls, the wolves circled and eyed her whenever she passed.

The tally of loss was getting worse all the time: down one dog, one father, one little brother, and one big bag of stupid gadgets that she’d never have gotten to work again anyway. Women knew things, all right. Everything except how to realize they were being lied to when it mattered most.

She tried to locate her father anyway and roved among his campsites. She found his blanket covered with fallen leaves, wrinkled her nose at the rotting residue of Tom Harkin scraped onto trees and logs. Found the last two platefuls of food, eaten, but so messily she couldn’t imagine they’d been eaten by anything human. Found, finally, the thing that convinced her he must be dead, because he would never have left it behind: a square of paper folded and unfolded ten thousand times before being nailed to one of the trees with a thorn. A pencil drawing of her and Jeremy, just their faces, younger by two or three summers, his beneath hers and her hair sweeping down around him like protective arms. She’d forgotten her father had drawn it. Forgotten he even could.

She kept it. But knew it would be years years years before she could unfold it to look at again.

She felt worst of all for her grandfather. He never wanted to leave his post on the wall at all now. Little runaway boys had to come home sometime.

As, within the village, the wolves gathered, biding their time for attack.

She watched them from the windows and locked doors of the trailer where she no longer lived, where nobody lived anymore, a home that had fed its people one by one to the ground and the woods until she was the last one left, and if the men had their way, she probably wouldn’t be long in following. One way or another. She watched them go about their days, rough and unshaven, their hands like tree bark and cruelty in their laughter. They breathed with the arrogance of men who knew exactly how much they could get away with. They celebrated it in every step.

Even the tiniest victory over them had to be better than nothing.

She found Miles McGee before any of the rest of them had a chance to split her apart from the herd. Miles was still a year older than she was, and still most of his life the closest thing she had to a big brother, and still starting to look at her differently. Which she was now glad of, finally liking it more than not, because what choice did she have? Nothing was more futile than wanting things to stay the same when you knew nothing ever did.

“There’s something I’ve got that I can only give away once,” she told him, standing on tiptoe, leaning into this tall boy who looked like pole beans should be growing on him; who had brought her books from faraway places. “And if I do, that means nobody else gets to take it.”

It was a minute before he understood what she meant.

Apparently they started going dumb pretty early.

Unlike Miles, she didn’t sleep that night afterward, or if she did it was the kind of sleep where all you did was dream you were wide-awake, so they cancelled each other out. Both states felt the same, lying there a little sore, sort of throbbing, kind of warm, a lot scared.

Tara wouldn’t be scared, she thought. Tara would move right along and go back to tampering with the balance of nature.

Melody knew she had to have slept some, though, sliding awake a little at a time. How else could she explain only gradually becoming aware there was screaming going on outside, and that it must’ve been going on for a while, because her dreams had been making it their own.

Her eyes popped open in what passed for dark on a night with this much moon showing. She listened to the echoing sound of a shriek that built and built and seemed to whiz from one side of the village to the center, a man’s but faster than a man could run, ending with a guttural crescendo, as if the last scream exploded out of him with terrible violence, then abrupt stillness.

Fully awake now, she listened for more, like listening for a crack of thunder from a passing storm, and for a moment doubted she’d really heard anything at all.

At her side, Miles turtled his head from beneath the covers and propped himself back on his elbows and peered around in the gloom. “Were you having a bad dream? Was that you mak—”

“Shush yourself.” She popped a fingertip to his lips like she’d been doing it all her life, as she heard the hubbub of the village coming awake around them, jumpy and panicked and full of fraying nerves. “You think we should . . . ?”

“Melody,” he whispered through his teeth, not moving his mouth, the way you sound when you don’t want to move anything at all. “What’s that at the window?”

The trailer’s bedroom had only one. She flicked her gaze toward it and tried to put it together, something sensible out of the pieces that, on their own, may have been familiar, but not like this. Her breath locked in her throat when she saw the face tilt to one side, its ragged beard scraping the glass like wire bristles. Hands were clutching the window, four of them, one high on each side and two more below. Pinpoints of moonlight glinted as it blinked.

She followed where its baleful gaze seemed directed, not at her but at her side. Miles. It was looking at Miles. The shadows on its face deepened as it scowled and its brow furrowed with wrath, and then there was a grimace full of teeth, twice as many teeth as she’d ever seen in even the broadest smile, and the nails of one hand screeched along the glass. The hand withdrew and she was sure it turned into a fist then, and she knew what was going to happen next. Because women knew the worst kinds of things.

Before it could go any farther, she threw both arms around Miles, pulling him tight to what on any other girl might have been called a bosom. No, she said to the window, a word without sound, a silent word and pleading eyes. No. It’s not like that. Don’t.

After a moment the oversized face relaxed, the shadows lightening and the grimace disappearing and the eyes content to stare. It pressed a hand to the glass, then all of it was gone, the face rising up and away, rising, and that was the most impossible thing of all, because the window was, what, seven feet off the ground. Which meant that this visitor was stooping.

Her father, whatever he was now, had been stooping.

You could never throw on clothes fast enough when you really needed to. Melody made do with as little as she could get away with and let a blanket cover the rest. Then she was out the door, the frosty ground cold on the soles of her feet, sprinting around behind the trailer and finding nothing, hearing only the crash of hurried footsteps. She followed the ruckus of them to a lonely eastern stretch of the wall, got there only in time to see something slipping over the top, a leg, one freakishly long leg, there, then gone.

As a galaxy of stars spun slowly overhead, she stared after this interloper as though it would return, but things like that never came back for a better look. They did what they did, then let the night swallow them whole.

And to find out what it had done, what it had truly come for, all she had to do was follow the voices and lanterns’ glows to the heart of the village. Miles was there already, because he said that’s where he thought he would find her, except he hadn’t, and there was such relief on his face that she thought maybe there was a chance she could love him, because when he looked at her she could tell that the last thing he was seeing was just a body.

With a gliding sense of disbelief, she walked around and around the Thieves Pole, Miles at her side, no trouble keeping up, because most of her energy went to trying to comprehend. Just trying to fathom the sight. She had trouble enough keeping her jaw closed.

It was all a blood-slick tangle of arms and legs, some clothed, some bare, others so soaked and mangled she honestly couldn’t tell. She found it impossible to discern how many there were until she counted the heads jutting from the stack in different places. Seven. Seven men, skewered one by one over the Thieves Pole, like fish that had been speared and left to accumulate along the shaft.

Except the Thieves Pole was eight feet high if it was an inch, meaning that whatever had done this was . . . well, tall enough to have to stoop when looking into trailer windows. And climb over their wall without much bother.

Hunsicker? He was there. He was on the bottom, had been the first to go.

Turning her attention to the living, she glanced from face to face, friends and neighbors every one, their features distorted in the whirling light of the lanterns, dumbfounded, sick, and horrified.

I guess you’ve got your limits after all, she told them from her heart’s deepest chamber. And if you’ve got a problem with this, you already know what to do. Just turn your heads and pretend you don’t see a thing. You’re so good at it.

The only ones whose faces were harder to read were young and female, girls like her. At some point in her orbit around the Thieves Pole, Miles dogging her steps, she found herself next to Jenna Harkin, huddling inside a worn, old parka that had lost half its goose down. Melody stopped, finally, and their shoulders knocked, and Melody wiggled her fingers at her side until Jenna clasped her hand.

“It’s right they’re there,” Jenna said, just loud enough for Melody to hear, and no one else. “They were thieves too. Same as anybody who took something while another person’s back was turned.”

But by the time she spat at the corpses, she didn’t seem to care who saw.

Later, when the crowd began to break up and people started talking about ladders and the best way to lift the bodies off the pole, Melody told Miles to go on back to the trailer, their trailer—right, he could consider it theirs if he wanted to—and that she would be following soon enough. But first there was something she needed to do.

And bless his heart, she felt his eyes watching her back until she turned a corner and knew she was lost from sight.

Along the northern stretch of wall, she climbed the steps to the watchtower where her grandfather sat waiting. She didn’t come without guilt, tons of it, because she’d caused him more grief lately than a grandfather should have to bear. But she couldn’t think about that now. He smiled at her and fed a few hunks of wood into the stove and held his hands to the crackles and sparks before leaving the iron door open. A fire was nice to watch sometimes.